To calculate the value we create, the entire world turns to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). GDP measures the total value of goods and services produced within a country’s borders in one year. Over the past 50 years, global GDP has increased 30-fold. That’s enormous. When adjusted for inflation, the figure is still a factor of 5 or 6. Adjusted for population growth (there are more of us producing), it’s 2 to 3 times higher per capita. As for the median, which helps us understand wealth distribution, it is somewhat lower depending on the country. Still, for each person, the capacity to create value is nearly twice what it was in 1970.

However, during the same period, the ecological deficit has also doubled. In a single year, we consume roughly twice what the planet can regenerate. “GDP has grown at the expense of the planet,” concludes economist Diane Coyle. While we feel as though we are “creating” value, it would be more accurate to say that we are “relocating” it, from its ecological bedrock to our consumer societies.

Something is Rotten in the Kingdom of Measurement

How did this happen? First, because GDP is not the right measure of value. Its inventor, Simon Kuznets, warned that it could “hardly serve to assess the well-being of a nation.” Furthermore, GDP is “a wartime metric,” adds Diane Coyle. “It doesn’t account for domestic work or nature. In wartime, a standing tree adds nothing to GDP until it is cut down and exploited.” GDP also doesn’t measure “our common sense, our courage, our wisdom, or our learning, nor does it measure our compassion or our devotion to our country. It measures almost everything except that which makes life worth living,” as Robert F. Kennedy noted in a speech that ultimately cost him his life.

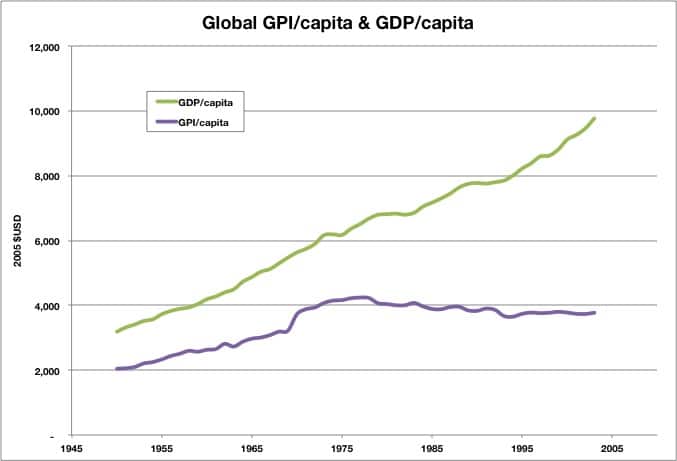

To account for what GDP leaves out, an alternative indicator was created: the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI). The GPI adds to GDP the estimated value of non-market economic activities, such as domestic work, family care, and volunteer activities. It then subtracts the estimated value of natural resources lost (environmental damage, depletion of non-renewable resources, etc.) and social damages (unemployment, crime, accidents, illnesses, etc.).

The difficulty of truly creating value becomes clear when looking at the graph comparing GDP and GPI. A “decoupling” of the curves appears in the mid-1970s: while GDP continues to rise, Genuine Progress stagnates and then declines (Ida Kubiszewski et al., 2013). From that point on, the wealth of nations no longer translates into improved lives. The “value” created by the economy ceases to be real “value” because it no longer contributes to the well-being of those whose activity it reflects—us. And yet the curve rises. There is, indeed, something rotten in the kingdom of measurement.

The Value We Need

And the world feels it. The economic crises of the 1970s (oil shocks) and 2000s (the dot-com bubble, the 2008 financial crisis) have shaken confidence in the purely material benefits of consumption and work. Even the most conservative progressives now acknowledge that economic value alone can no longer be considered the only measure of worth. According to the World Economic Forum, we must now evaluate innovation (adapting to disruptions), inclusivity (ensuring dialogue with all stakeholders), sustainability (aligning with the planet’s limits), and resilience (bouncing back from future crises). “We must transition from the growth we have to the growth we need” (WEF, 2025).

On an economic scale, it makes sense to preserve the resources upon which growth depends. But what about a company? Its primary focus remains generating economic value. If I create immense value for the planet but cannot pay my employees, I go bankrupt. Similarly, an impact-driven company is not guaranteed economic success. And rejecting a cheaper, albeit controversial, resource risks giving the advantage to competitors.

This complex situation manifests within businesses as a growing sense that each year is harder to navigate, that every point of growth is a battle, and that everything—regulators, employees, and consumers alike—seems to conspire against them, making it increasingly difficult to operate peacefully.

A Measure of the Desirability of Things

Creating significant value is still possible—provided we shift from the value we have to the value we need. The value we need is the one that stabilizes economic, political, and environmental systems: the one that raises the Genuine Progress Indicator. It emerges from valuing actions that contribute to these goals, as value ultimately measures what we desire. To “value” something means to “find desire for it.” This kind of value will guide our investments, career choices, and aspirations for our loved ones.

It’s not our actions or production themselves that hold value, but their potential: what our actions or production enable and the world they make possible. It’s not the price or the exchanged object itself that “counts,” but the deeper meaning that people assign to the act (producing, giving, exchanging, helping, recycling, consuming, etc.). To evaluate is to lay ourselves bare, to reveal who we are, what we believe in, and what we want to see matter in the world. A KPI is never neutral. A company with a “culture of kindness” that only measures cash flow actually has a culture of cash flow.

As we see our desire grow for organic products, cycling, the circular economy, social innovation, or volunteerism, society begins to see their value grow as well.

How, Then, Can We Easily Create Significant Value?

Businesses Can Quickly Create Value. Companies have many opportunities to generate significant value through a variety of actionable verbs that open pathways for growth: fostering togetherness, rebuilding social ties, restoring trust, regenerating ecosystems, putting resources into circularity, supporting the vulnerable… But also by innovating to meet the demands of the times, collectively deciding what matters, leveraging strengths to build resilience, enhancing performance through diversity, rethinking accounting frameworks to incorporate natural and social capital, pooling interests to ensure resilience, or contributing to the normalization of a regenerative economy. Even in periods of economic stability or slow growth, progress in these areas attracts talent, consumers, and investors. Nothing holds greater value than moving in the direction of history.

Where to Begin? Start by seeing products and services as interactions, not as finished goods (D. Graeber, 2001). They are born and evolve through a collective narrative that places them in the market and within the imagination of a community. They are opportunities for shared experiences. Their value, therefore, depends on evolving cultural meanings (such as the rise of second-hand goods, which in just a few years have shifted from being seen as discount options for the underprivileged to becoming new avenues for growth).

Admittedly, the economic climate is challenging (low growth, rising labor costs, a gloomy business outlook…), but countless action verbs already exist to help create the value we need. Businesses are not merely responsible for the products and services they bring to market. They are also the authors of the world that these products and services make possible.