When we think of Alan, we mostly think of its collaborative culture. Do you know why?

Indeed, the culture of collaboration is central, but it's also the product culture. When our two co-founders created Alan, they created two products: Alan, the health insurance company, and, in parallel, they built its corporate culture.

One of the founding pillars of our corporate culture is radical transparency. This means that all information is made available to every employee. We believe that having no secrets helps avoid gossip and inefficiencies. It’s also considered a prerequisite for autonomy and accountability.

The two products—our service and our culture—feed into and support one another. Nothing was born from theory or designed without purpose. The way we solve problems and design processes is deeply rooted in our values, which we use in our daily operations.

What are these values?

There are five, and they evolve over time. First, we have distributed ownership. Each person, depending on their level of expertise and seniority, is in control of their scope. The second is prioritizing our members. We focus on needs, seamless experiences, and delivering value. Then there's radical transparency. The only information that isn’t transparent is personal employee data. Next is personal and collective growth. We emphasize the value produced as a team rather than individual performance. Finally, we have ambition without fear. This value was introduced recently. Alan is in hypergrowth, and, in practice, it’s a team of people striving for excellence daily. It’s quite demanding! It involves thinking about the intensity of work.

From your experience at Alan, how would you define corporate culture?

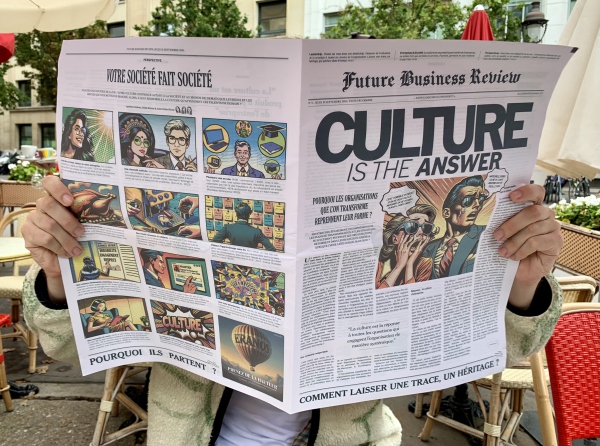

Culture is simply what defines your playing field—the framework within which teams operate. It determines what they can achieve, or not. For instance, it sets the foundation for how we handle intensity at work. This framework is not dogmatic; it requires a lot of case-by-case consideration. In fact, culture is a core product of the company.

❝When our two co-founders created Alan, they developed two products: the health insurance service and its corporate culture.❞

Today, companies that only produce a product or service offer a very poor candidate-employee experience. Culture needs to be treated as a product because it enables a user-centric approach. You start with needs and create this “product,” which is the corporate culture, around them. Companies need this coherence because they must craft a narrative that goes beyond their product if they want to build their employer brand.**

At Alan, most of our employees are in their thirties, working in tech. It’s a reflective environment that values the alignment between words and values.

Does calling it a product imply that corporate culture can be controlled? Is that really the case?

It’s not an industrial product, it’s a living product. There’s almost a craft-like quality to how it’s designed. It’s living because we’re talking about people who have opinions on issues that concern them directly. You have an idea in mind, and you have material to work with. And this material is alive.

You might have a certain vision of the final product, but events will disrupt your plan, and you’ll need to adjust. The challenge is to guide its development without stifling it. That doesn’t mean you don’t end up with a product—you do, but it’s an evolving one.

The idea is that we have people who are constantly in motion. And again, beyond the practical benefits, I like the idea of people being happy, curious, and excited to come in every morning. Otherwise, it doesn’t make sense.

Do companies have a role to play through their culture in contributing to the world’s livability?

I wouldn’t generalize. At Alan, our corporate culture is centered around autonomy, problem-solving, and the ability to learn and take on complex issues independently. I find this culture extremely powerful.

Take climate change, for instance—it’s an overwhelming issue that weighs heavily on everyone. At Alan, we’d ask, “How can I break this down into smaller problems and tackle them one by one to have incremental impact and act at my level?” Or, “How can I do this autonomously? How can I activate the resources around me to make it happen?” For me, this creates people who, in theory, are fully capable of tackling today’s and tomorrow’s challenges.

Any final thoughts?

Alan’s culture isn’t perfect, and it’s not for everyone. But it has the merit of being clear and embodied. Like in any company, we’ve had people leave disappointed. But I’ve never seen anyone leave because they didn’t find what was promised to them in their employee experience.

Encouraging companies to develop a culture treated like a product isn’t just a theoretical exercise. If you don’t know how to guide the collective, if you don’t control the playing field you’re offering them, the company moves forward like a headless chicken. It lacks meaning, and people need meaning. They need coherence and accountability.

Many leaders feel stressed, wondering how to make up for lost time if they didn’t focus on company culture from the start. Yes, it can be implemented later. But it must be done with true honesty. Without full commitment from top leadership, it’s pointless.